8 Genomic Specialists

⬜ Developing Hypotheses

⬜ Sample Collection

🟩 Outbreak Investigation

⬜ Sequencing

⬜ Bioinformatics

⬜ Molecular Epidemiology

⬜ Public Health Implementation

A Multidisciplinary team of Genomic Specialists and Disease Inestigators were assigned to investigate the mystery flu-like outbreak in Fuchsia City/Safari Zone:

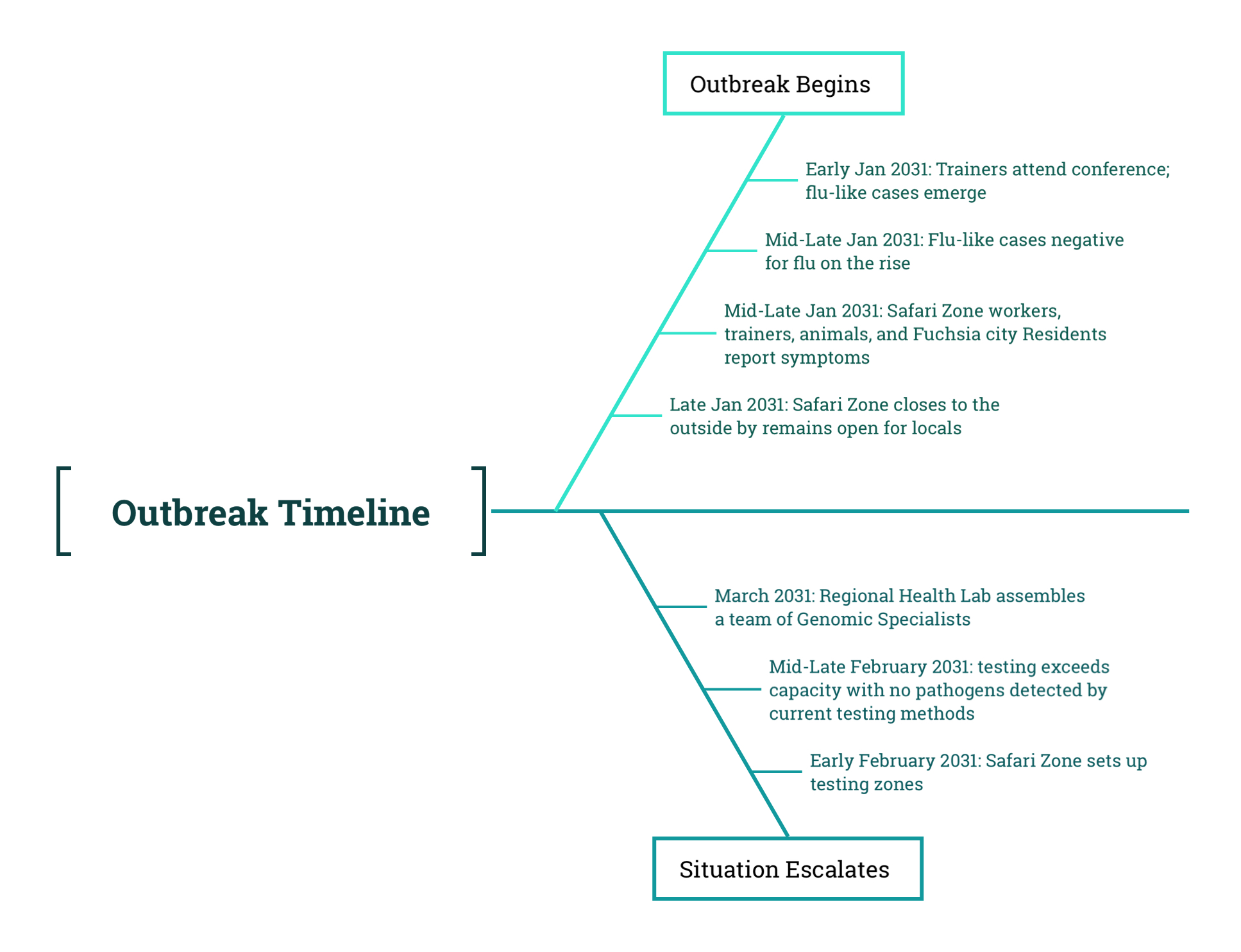

As the outbreak intensified and local testing efforts failed to identify a cause, the doctors, animal trainers, and public health officials in Fuchsia City realized they needed support. They reached out to the Regional Health Laboratory, a centralized state-level facility responsible for assisting local health districts with high-complexity testing and outbreak investigations. Unlike neighborhood clinics or hospital labs, the Regional Lab had both the infrastructure and the expertise to investigate complex or unusual pathogens.

In response, a multidisciplinary team of Genomic Specialists was assigned to the case. This team included:

- Microbiologists, who specialize in laboratory testing and sequencing workflows. They are responsible for extracting genetic material from samples, preparing libraries, and operating the sequencing platforms.

- Bioinformaticians, who process and analyze the raw sequencing data. They use computational pipelines to assemble genomes, identify mutations, classify organisms, and generate outputs that can be interpreted by downstream analysts.

- Molecular Epidemiologists, who interpret those outputs in a public health context. They perform sequence alignments, construct pairwise distance matrices to compare how genetically similar cases are, and build phylogenetic trees to visualize relationships between cases over time and space.

The multidisciplinary team included expert Disease Investigators as well:

- Zoonotic Epidemiologists and Local Health Jurisdiction Epidemiologists, who provide field-level insights and help link genetic data from humans to animals observed in the Safari Zone.

Each of these roles adds a layer of insight. Together, they help uncover not only what pathogen is present, but also how it is changing, who may be connected, and what interventions might be needed to stop its spread.

8.1 Regional Lab Capacity

The Regional Health Lab was equipped to perform a range of sequencing strategies. These included:

- Short-read sequencing, which offers high accuracy for detecting single nucleotide variants.

- Long-read sequencing, which is used for assembling entire genomes and identifying larger structural changes.

- Shotgun metagenomics, which sequences all the genetic material in a sample and is especially useful when the pathogen is unknown or difficult to culture.

FOR DETECTIVES WHO WANT MORE:

How sequencing technologies actually work:

- Short-read (Illumina)

- How it works: Fragments DNA into 300bp pieces, attaches fluorescent tags, and reads bases via camera as they’re added strand-by-strand.

- Outbreak use: Gold standard for SNP detection (e.g., tracking hospital transmission chains).

- Trade-off: Can’t resolve large structural changes (>50bp).

- How it works: Fragments DNA into 300bp pieces, attaches fluorescent tags, and reads bases via camera as they’re added strand-by-strand.

- Long-read (Oxford Nanopore/PacBio)

- How it works: DNA threads through nanopores or polymerase enzymes, detecting electrical signals (Nanopore) or fluorescent pulses (PacBio) for continuous reads up to 1Mbp.

- Outbreak use: While possible in short-read sequencing, in long-read sequencing it is easier to capture recombination events in novel viruses (critical for muubat spillover investigation).

- Trade-off: Higher error rate (~5-15% vs Illumina’s 0.1%).

- How it works: DNA threads through nanopores or polymerase enzymes, detecting electrical signals (Nanopore) or fluorescent pulses (PacBio) for continuous reads up to 1Mbp.

- Shotgun Metagenomics

- How it works: Sequences ALL DNA/RNA in a sample (host, pathogen, microbes), then computationally filters to find viral fragments.

- Outbreak use: When PCR fails (unknown pathogen) or culture isn’t possible.

- Trade-off: Often will not get full length genome sequences; therefore the data are great for pathogen detection, but may not be readily useable for investigating relationships between cases

- Pro tip: Viral enrichment (e.g., rRNA depletion) boosts pathogen signal 1000x.

- How it works: Sequences ALL DNA/RNA in a sample (host, pathogen, microbes), then computationally filters to find viral fragments.

In addition to sequencing platforms, the lab maintained a suite of bioinformatics pipelines designed to transform raw data into usable insights. These pipelines typically include:

- Quality control, to filter out poor-quality reads and contaminants.

- Read alignment or de novo assembly, to reconstruct genomes by either mapping reads to a known reference or assembling them from scratch.

- Taxonomic classification, which uses reference databases to identify the organism or organisms present.

- Mutation detection and annotation, which catalogs genetic differences and assesses their potential biological or epidemiological significance.

These outputs are then used by Molecular Epidemiologists to investigate whether certain sequences are closely related, how the virus may have spread between hosts, and whether transmission clusters or spillover events can be inferred from the genetic data. While they typically rely on genome assemblies or other processed sequencing outputs prepared by Bioinformaticians, Molecular Epidemiologists are also capable of performing genomic analyses themselves. These may include generating pairwise distance matrices, constructing phylogenetic trees, or conducting other comparative analyses that help link genetic variation to patterns of transmission and exposure.

The team coordinated with doctors and animal trainers to have swab samples shipped from across Fuchsia City and the Safari Zone. Samples included those from symptomatic humans, trainers, Safari Zone workers, and affected animals such as felines, canines, ducklings, and the two bat trainers.

| Host | Number of Samples |

|---|---|

| Humans | 23 |

| Felines | 5 |

| Canines | 6 |

| Ducklings | 4 |

Table showing the number of swab samples collected and shipped to the Regional Health Lab.

Most of the samples came from symptomatic individuals and visibly ill animals, though a few were collected from individuals who had been exposed but were not yet showing symptoms. Samples collected in February were reviewed for quality, and only those with sufficient material were retained for sequencing. The majority of high-quality samples came from January and early February, when active archiving had begun.

This stage of the investigation marks a critical shift in the outbreak response. Earlier phases focused on observing symptoms, collecting samples, and forming initial hypotheses. With the involvement of the Regional Health Lab, the investigation now moves into testing, sequencing, bioinformatics, and molecular epidemiology. These steps are foundational to understanding the genetic characteristics of the pathogen and informing a targeted public health response.

8.2 Discussion Three: Choosing the Appropriate Sequencing Technology

The Regional Health Lab has the ability to culture bacteria and viruses and perform several types of sequencing, including short-read sequencing, long-read sequencing, and shotgun metagenomics. In this investigation, standard diagnostics have failed to detect a known pathogen, and there is concern that a novel virus or bacterium may be responsible for the outbreak.

Based on what you know about the lab’s capabilities and the types of samples collected, what sequencing platform or combination of platforms would you use for initial identification? How might your choice differ depending on whether the goal is to detect something completely unknown versus confirm the presence of a suspected agent? Be sure to explain the strengths and tradeoffs of your approach.

8.3 Discussion Four: Deciding upon Bioinformatic Analyses

Once sequencing is complete, the raw data must be processed and interpreted. This is where bioinformatics becomes essential. Using your proposed approach from Discussion Three, what types of bioinformatics methods or analyses would you apply to identify a novel pathogen? Consider how you would handle unknown organisms, what kinds of tools or reference data you might use, and how you would distinguish true findings from background noise or contamination.