6 Fuchsia City begins collecting…

⬜ Developing Hypotheses

🟩 Sample Collection

⬜ Outbreak Investigation

⬜ Sequencing

⬜ Bioinformatics

⬜ Molecular Epidemiology

⬜ Public Health Implementation

Fuchsia City begins collecting swab samples from the animals, workers, and residents:

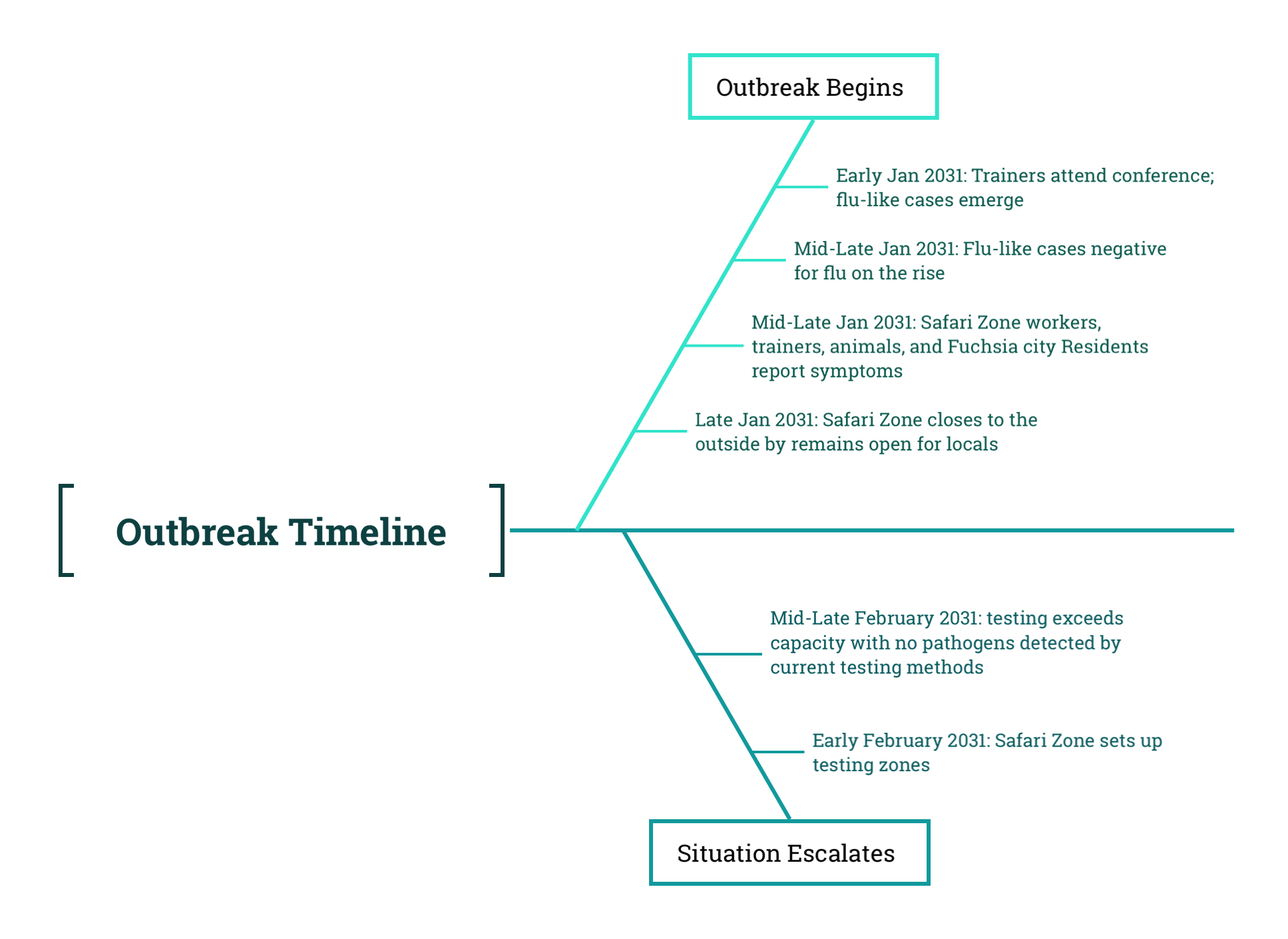

By the end of January, as the Safari Zone closed to outside visitors, hospitals across Fuchsia City were reporting a sharp rise in residents experiencing flu-like symptoms. The surge quickly overwhelmed local clinics, and demand for testing exceeded what the city could provide. Most symptomatic individuals were screened for influenza, but many of those tests came back negative. Doctors could offer only supportive care unless a patient’s condition became severe.

To broaden coverage, the city established temporary testing stations throughout Fuchsia City. These community-based sites primarily relied on antigen-based rapid tests, which detect specific proteins produced by viruses and can deliver results in minutes. However, these tests are less sensitive than molecular methods and do not retain any genetic material for further analysis. In contrast, clinical sites inside the Safari Zone had access to PCR testing, which detects the genetic material of pathogens and can preserve samples suitable for sequencing if handled properly. Still, even with PCR testing, many samples from symptomatic individuals tested negative for all known respiratory pathogens.

As previously reported, animals in the Safari Zone had also begun to show signs of illness, including fever, lethargy, and loss of appetite. In response, the city expanded its testing efforts to include wildlife. Special clinics were established in different zones of the Safari Park to monitor affected species. Animals displaying symptoms were swabbed and tested for flu using PCR-based respiratory panels. These efforts mirrored what was being done for symptomatic residents, but the results were similarly inconclusive. Most human and animal samples continued to test negative.

At this point, all testing had been focused on known pathogens. No sequencing had yet been performed. Most diagnostic samples were used up during testing or discarded afterward. The system had been built to support clinical decision-making, not molecular investigation. As a result, there was little usable material for identifying what was causing the outbreak.

As the diagnostic gaps became more apparent, doctors and animal trainers began to suspect that they were dealing with a pathogen their existing tools could not detect. After meeting to discuss the next steps, they agreed to begin archiving swab samples not just for diagnosis, but for later molecular analysis. They also decided to contact the Regional Health Laboratory to determine whether it had the capacity to help identify the unknown agent.

Although thousands of people and animals were affected, it was not feasible to collect samples from everyone. Many early tests had not preserved any usable material, and PCR testing was only available in select locations. In practice, most of the archived samples came from individuals and animals who were actively symptomatic, particularly in areas where illness had already been reported. These were the cases that drew the most attention, given the visible signs of disease and limited resources for broader screening.

Fuchsia City had over a million residents and thousands of animals within the Safari Zone. With so many potential sources of infection and no confirmed cause, the public health teams faced a critical decision: which samples should be sent to the Regional Health Lab, and how should they be prioritized? Their choices would shape what investigators might find—or overlook entirely.

6.1 Discussion Two: Designing a Sampling Scheme

In an outbreak scenario like this, not every sample can be sequenced. Time, cost, and lab capacity are all limited. Public health teams must decide what kind of sampling scheme to use—that is, how to choose which samples to sequence in order to learn the most about the outbreak with the resources available.

In the story, sample collection was shaped by real-world constraints. Testing focused on symptomatic individuals, and sequencing efforts were based on whatever diagnostic samples were still usable. However, if you were planning a sampling strategy from the beginning, without those limitations, what would an ideal sampling scheme look like?

Describe the sampling approach you think would be most effective for understanding and controlling this outbreak. What do you want to capture, and how does your sampling strategy help you do that?

You might consider:

- Sequencing all available cases for a comprehensive view,

- Selecting a random or representative subset of samples for statistical inference,

- Focusing on specific populations, such as symptomatic individuals, geographic clusters, or particular animal species,

- Or combining more than one of these strategies.

Explain your reasoning. What insights would your scheme help uncover? What limitations or biases might it introduce?